Following deliberation on the public input on the National Health Insurance Bill, the Portfolio Committee on Health approved a list of amendments to the bill which was passed by the National Assembly on 13 June 2023. This article looks at the implications of the PCH decisions, and some possible courses of action.

There was an unprecedented level of public interest in the NHI Bill: the Portfolio Committee on Health (PCH) received more than 100,000 submissions and more than 130 requests from individuals, organisations and institutions to make oral presentations.

This was accompanied by extensive public debate and comment on the issue in the media and social forums.

Respondents raised a wide range of concerns, as documented in Daily Maverick’s Health Bill series published in 2022 (See Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6). Concerns focused on:

- The viability and sustainability of the proposed funding model;

- Enhanced opportunities for corruption;

- The lack of separation of the political and operational spheres in the proposed governance structure, and

- The concentration of power in the minister of health.

Respondents were also concerned that the proposals contravened other legislation, particularly in terms of constitutional and human rights obligations, that it would restrict access and did not provide sufficient clarity on the benefits to be offered nor the process by which they would be determined.

Three options were open to the PCH after the public inputs:

- Pass the bill without any changes or with only minor amendments;

- Make substantive amendments to the bill to address concerns raised; and

- Reject the bill.

The PCH chose option one, making no substantive amendments in response to major public concerns. That being said, some minor amendments were made, largely to try to curtail ministerial discretion and powers, and to expand on definitions, using more precise language.

Consequently, potential constitutional infringements arising from designating the NHI fund as the sole funder and purchaser of health services for the country, nor the lack of clarity on benefits and access concerns, nor the contradiction between the bill and the constitutionally mandated role of provinces were addressed.

Moreover, the amendments shorten the timelines for the transitional arrangements from the original five years for phases one and two to three years for each phase – which is unrealistic given the scope of the changes required.

Implications

By deciding to approve the amended bill with mainly nonsubstantive amendments, the PCH has largely rejected public concerns. The deliberations on and approval of the amended bill took place on a divided party-political basis. The amended bill was supported in its entirety by the ANC and IFP PCH members, and rejected in its entirety by the DA, Freedom Front Plus and EFF members.

The amended bill was approved despite warnings from Parliamentary Legal Services that there could be a host of potential constitutional traps in the current composition of the bill. The risk of legal challenges is therefore high, with the DA, the Freedom Front, Solidarity, the Helen Suzman Foundation and the Free Market Foundation having already signalled this intention.

The failure of the amended bill to respond to the concerns flagged – by a range of business, funder and provider organisations – risks further eroding broader public support for the NHI, a critical requirement for its successful implementation.

In the longer term, if the negative outcomes predicted by those who have expressed concerns regarding the bill materialise, the healthcare system would be weakened rather than strengthened by the reform.

How do we proceed?

It is difficult to predict the outcome of the likely legal challenges and contestation around the amended bill. It must also still be signed by the President. It is also uncertain how long this will take to resolve. In the circumstances, what approach should be adopted for health services in the interim?

The uncertainty and inertia created by the expectation of an imminent, extensive – yet poorly defined – reform has arguably contributed to the progressive deterioration of public health services in most parts of the country and increasingly unaffordable and inefficient private health services.

Critical reforms necessary to improve and strengthen the healthcare system have not been implemented, in anticipation of the implementation of the NHI “magic bullet”, which –it was hoped – would address all the shortcomings of the health system, including governance, financing, workforce, quality, prioritisation and inequity.

Discussion of South Africa’s health reform needs to move beyond the simplistic division between those “for” and “against” NHI. The critical reforms required to strengthen the health system should be implemented immediately. These are necessary and overdue: they would improve healthcare immediately and would provide the essential building blocks for the NHI.

To illustrate the point, we provide four examples of reforms that need to be implemented immediately.

Legislative reform

The Health Professions Act of 1974 needs to be reformed to allow for alternative reimbursement models, group practices, etc.

The National Health Act needs to be reviewed to address issues including control of central hospitals.

The regulations related to the Office of Health Standard Compliance (OHSC) need to be reviewed, to allow the OHSC to play a foundational role in ensuring that our health facilities provide, and keep providing, safe and quality care to all in South Africa.

The Medical Schemes Act needs to be reviewed to address the extensive recommendations of the Health Market Inquiry, which to date have had limited implementation.

Sound and competent management, administrative and clinical oversight and governance

Changes take a long time to effect and we need to start the process by addressing the lack of separation between the political and operational spheres. While policy determination is inevitably a political process, technical competence should be the overriding concern in the operational spheres, including all appointments.

The National Digital Health Strategy, including the implementation of a common health patient registration system and health patient registration number for all residents (both public and private sector users), needs to be fast-tracked. Only through the establishment of an integrated IT platform can we start capturing the data necessary to plan for the health and healthcare needs of the country.

A comprehensive, pragmatic and accountable health prioritisation process should be funded and implemented to help the health service determine what services, interventions and technologies will be offered, to whom, and under what conditions and medical indications.

This can build on existing good practice in South Africa related to development of our National Essential Medicines List and Standard Treatment Guidelines. The concept of a “health services package” (i.e. lists, schedules, protocols and guidelines) is a critical element of the NHI, and indeed essential for any health system seeking to plan for and provide equitable, efficient and sustainable care.

International experience indicates that health prioritisation systems take many years to develop procedural and technical skills and knowledge, so the development of this capacity should be initiated as soon as possible.

Enable, don’t detract or delay

These examples could all be implemented as part of the ongoing strengthening of the health system, while at the same time creating an enabling environment for the implementation of the NHI.

The ongoing debate around the NHI journey is likely to attract significant attention from the public and health service actors, but it should not detract from or delay the specific, practical and uncontroversial actions that can be taken to improve health system performance and the health of the people of South Africa today. DM

This is the seventh and last article in our series about different issues dealt with in public submissions to Parliament on the NHI Bill. See Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6.

By Geetesh Solanki, Neil Myburgh, Stephanie Wild and Judith Cornell

Geetesh Solanki is Specialist Scientist in the Health Systems Research Unit at the SA Medical Research Council, an Honorary Research Associate in the Health Economics Unit at the University of Cape Town and Principal Consultant at NMG Consultants and Actuaries. Neil Myburgh is Professor in the Department of Community Dentistry at the Faculty of Dentistry and WHO Collaborating Centre for Oral Health at the University of the Western Cape. Stephanie Wild is a postgraduate student enrolled for an MPhil in Public Law at the University of Cape Town. Judith Cornell is former Director of Institutional Development and Planning at the Nelson Mandela School of Public Governance at the University of Cape Town.

The opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of their institutions.

Original article available on the Daily Maverick Website

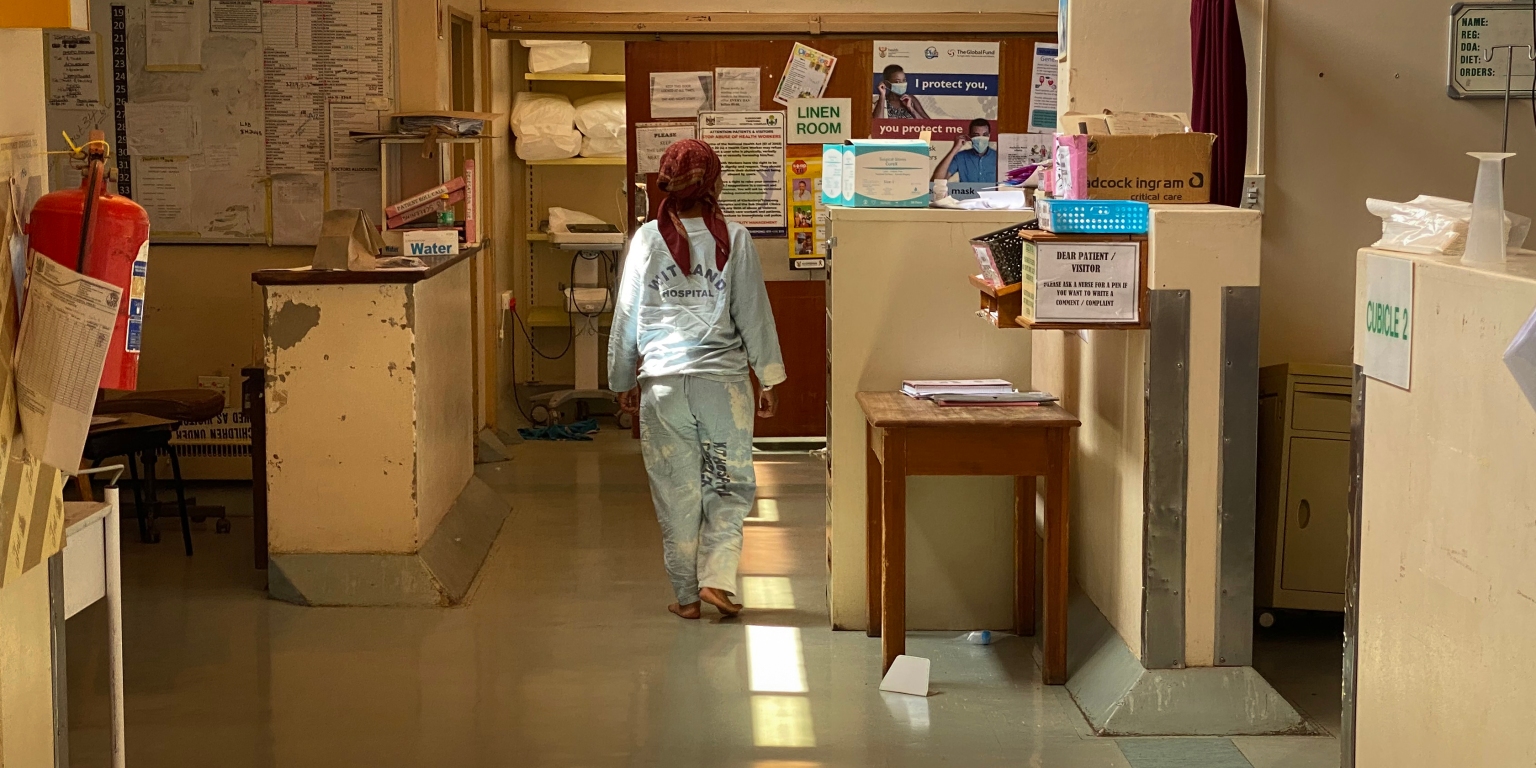

Photo credit: A patient walks in the hallway at Tshepong Hospital in Klerksdorp on 7 March 2023. (Photo: Felix Dlangamandla)